METTERNICH (Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar von).

Lot 10

Categories

Estimate:

EUR€600 - EUR€800

$645.16 - $860.22

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| No bidding increment | |

About Auction

Catalog Only

By Beaussant Lefèvre & Associés

Dec 13, 2022

Set Reminder

2022-12-13 08:00:00

2022-12-13 08:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Furniture and Works of Art from the Anne Aymone and Valery Giscard d’Estaing Collections

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/beaussant-lef-vre-associ-s/furniture-and-works-of-art-from-the-anne-aymone-and-valery-giscard-d-estaing-collections-11505

Beaussant Lefèvre & Associés contact@beaussantlefevre.com

Beaussant Lefèvre & Associés contact@beaussantlefevre.com

- Lot Description

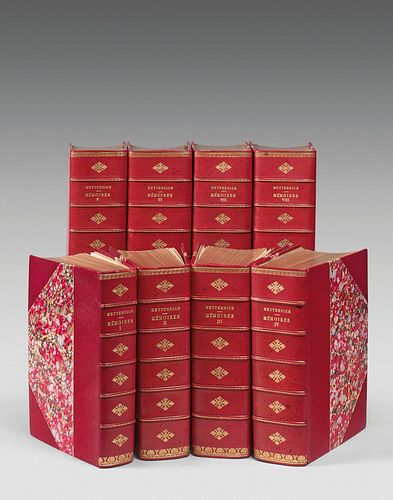

METTERNICH (Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar von). Memoirs, documents and various writings left by the prince of Metternich. Paris, E. Plon et Cie, 1880-1884. 3 parts in 8 volumes in-8, garnet half-chagrin with corners, spine ribbed with gilt friezes at the head and tail, gilt heads on witnesses, covers and spines preserved; spines slightly faded and spotted with minor snags (modern binding).

FRENCH ORIGINAL EDITION, ONE OF 20 NUMBERED HEADERS ON WHATMAN, the only ones on large paper

on large paper with 60 on hollande. Etched portrait-frontispiece. The work appeared concurrently in German (Vienna, Wilhelm Braumüller) and in French (Paris, Eugène Plon), while an English edition was discontinued in 1882 at volume V (London, Richard Bentley & son).

Extensive publication of the papers of the Prince of Metternich, including among others a memorial essay,

"Matériaux pour servir à l'histoire de ma vie publique, 1773-1815" (vol. I, pp. 1-215), and excerpts from the diary of his last wife Melanie Zichy-Ferraris, married in 1831 (spread over several of the volumes). Two analytical indexes make it possible to take advantage of this important mass of material. The editing work was carried out by the prince's son, Richard von Metternich (who was himself Austrian ambassador to the court of Napoleon III from 1859 to 1870), assisted by the imperial historiographer Alfons von Klinkowström.

THIS BOOK IS ONE OF THE MAJOR SOURCES ON EUROPEAN HISTORY, FROM THE NAPOLEONIC ERA TO THE REVOLUTIONS OF 1848. The son of a diplomat, Prince de Metternich (1773-1859) himself entered the career under the Consulate, and was Austrian ambassador in Paris from 1806 to 1809 before being appointed to the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs, which he held until 1848: he played a major role throughout the period, particularly in the establishment of the international balance of power that prevailed from the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) until the "Spring of the Peoples. Educated at the school of the Aufklärung, the prince promoted an enlightened despotism and a rational conservatism in a Europe that he dreamed of as federalist. The two fundamental principles on which he based his foreign policy were those of balance and legitimacy, and as such he was hostile to the notion of the nation state, opposing the hegemonic will of Prussia in Germany and the unification of Italy.

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB