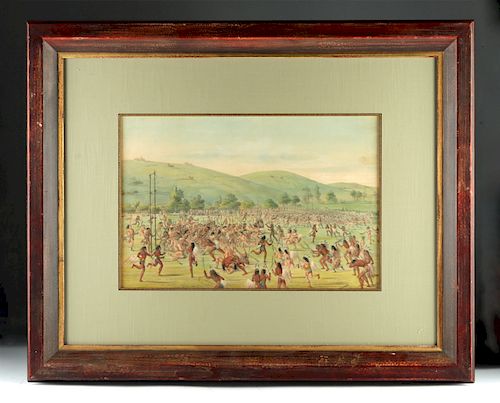

George Catlin Lithograph Ball-Play of the Choctaw 1875

Lot 133

About Seller

Artemis Fine Arts

686 S Taylor Ave, Ste 106

Louisville, CO 80027

United States

Selling antiquities, ancient and ethnographic art online since 1993, Artemis Gallery specializes in Classical Antiquities (Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Near Eastern), Asian, Pre-Columbian, African / Tribal / Oceanographic art. Our extensive inventory includes pottery, stone, metal, wood, glass and textil...Read more

Estimate:

$9,500 - $14,250

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $300 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $20,000 |

About Auction

By Artemis Fine Arts

Oct 11, 2018

Set Reminder

2018-10-11 10:00:00

2018-10-11 10:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Exceptional Antiquities | Ethnographic Art

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/artemis-gallery/exceptional-antiquities-ethnographic-art-3500

An important one-day auction featuring museum-worthy examples of classical antiquities, ancient and ethnographic art from cultures encompassing the globe. Artemis Fine Arts info@artemisfinearts.com

An important one-day auction featuring museum-worthy examples of classical antiquities, ancient and ethnographic art from cultures encompassing the globe. Artemis Fine Arts info@artemisfinearts.com

- Lot Description

George Catlin (American, 1796-1872), "Ball Play of the Choctaw, Ball Up", probably London: Chatto & Windus, ca. 1875. An original hand-colored lithograph from a deluxe limited edition of Catlin's "North American Indian Portfolio," among the most significant accounts of Native American life, printed by Day & Haghe, set in a custom frame under glass. Catlin's oeuvre stems from a lifelong fascination with Native Americans and a desire to preserve, in his words, "the looks and customs of the vanishing races of native man in America" with his art. This passion took root when Catlin was just a nine-year-old boy; exploring the woods of southcentral New York along the Susquehanna River in 1805, he came upon an Oneida Indian who greeted him in a warm, kind-hearted manner. This memory purportedly stayed with the artist throughout his career. Size: 16.5" W x 11.75" H (41.9 cm x 29.8 cm); 28.5" W x 23.75" H (72.4 cm x 60.3 cm) with mat and frame

Native Americans created the game of Lacrosse, though their version of the game was considerably different than the one played today. Oftentimes violent, it had very few rules, and was actually called "little brother of war" in Choctaw. The sport tested endurance, agility, strength, and skill. This image portrays hundreds of Choctaw men and boys playing a game similar to lacrosse near Fort Gibson, Oklahoma - their agility, skill, strength, and endurance on display.

Catlin's oil on canvas of this composition hangs in the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. The Luce Center Label reads as follows, "In 1834, George Catlin witnessed Choctaw lacrosse in Indian Territory near present-day Oklahoma, and was captivated by the game. He described ball-play as 'a school for the painter or sculptor, equal to any of those which ever inspired the hand of the artist in the Olympian games or the Roman forum.' Lacrosse, which involved a no-holds-barred struggle for the ball, was a physical, even violent, game called 'little brother of war' in Choctaw."

Despite the fact that Catlin had no formal training as an artist, he did have an undeniable raw talent for drawing. Although his father encouraged Catlin to study law instead of art, the legal trials were far less interesting to Catlin that the imagery before him. Catlin found himself sketching judges, offenders, and jury members, and within a few years time, he decided to sell his law books and move to Philadelphia to pursue art. Lacking direction, he painted portraits but was dissatisfied with these subjects until, in approximately 1828, a delegation of Native Americans stopped in Philadelphia en route to Washington, D.C. and Catlin was reportedly drawn to what he described as "their classic beauty." Seduced by the romance of the "disappearing races", Catlin recognized that smallpox and whiskey were decimating the indigenous peoples, and vowed that "nothing short of the loss of my life, shall prevent me from visiting their country, and of becoming their historian." So in 1830, Catlin headed West where he stayed for six years (returning East most winters to his family) and painted 300 portraits and almost 175 ritual scenes and landscapes. In 1837, following his return to New York, Catlin set up an exhibition in salon style (stacked from floor to ceiling) that made quite an impression.

As an artist, Catlin was both honored and criticized during his lifetime; however, the fact that he had created the largest of pre-photographic imagery depicting Native americans - a remarkable record - is undeniable. Bruce Watson, in his review of a 2002 Renwick Gallery exhibition of Catlin's work, wrote, "Though not the first artist to paint American Indians, Catlin was the first to picture them so extensively in their own territories and one of the few to portray them as fellow human beings rather than savages. His more realistic approach grew out of his appreciation for a people who, he wrote, 'had been invaded, their morals corrupted, their lands wrested from them, their customs changed, and therefore lost to the world.' Such empathy was uncommon in 1830, the year the federal Indian Removal Act forced Southeastern tribes to move to what is now Oklahoma along the disastrous 'Trail of Tears.'" (Bruce Watson, "George Catlin's Obsession," Smithsonian Magazine, December, 2002)

In a famous passage from the preface of his "North American Indian Portfolio", Catlin describes how the sight of several tribal chiefs in Philadelphia inspired him to record their way of life: "the history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy of the lifetime of one man, and nothing short of the loss of my life shall prevent me from visiting their country and becoming their historian". Understanding that the Native Americans' future was in jeopardy, Catlin he worked tirelessly, always feeling the pressure of time, to record what he saw - an artist-as-ethnographer. From 1832 to 1837 Catlin sketched the tribes during the summer months and during the winters he would paint the imagery in oils. In addition to exhibiting these, he published a selection of the finest of images from this record in the "North American Indian Portfolio" in order to expand his audience. "Buffalo Hunt" was part of this publishing venture.

Provenance: private Lucille Lucas collection, Crested Butte, Colorado, USA

All items legal to buy/sell under U.S. Statute covering cultural patrimony Code 2600, CHAPTER 14, and are guaranteed to be as described or your money back.

A Certificate of Authenticity will accompany all winning bids.

We ship worldwide and handle all shipping in-house for your convenience.

#134051Slight wear to the frame with scuffs as shown, but otherwise very good; mat and UV protection glass are very good as well. The lithograph appears to be in generally excellent condition. It has not been examined outside the frame.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

All shipping is handled in-house for your convenience. Your invoice from Artemis Gallery will include shipping calculation instructions. If in doubt, please inquire BEFORE bidding for estimated shipping costs for individual items.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB