What is the Mysterious Mandala? - (Kinda) Explained

One of the most important and mesmerizing designs in Asian art is the geometric diagram known as a mandala.

You might not be that familiar with the term ‘mandala’, but its presence has been recently popularized in pop culture from tattoos, to adult coloring books to the protective Tao Mandala shields used by characters in Marvel’s superhero movie Doctor Strange.

Let me explain what is a mandala and what does it mean? In Sanskrit (considered the world’s oldest language), a mandala can be translated to ‘circle’ and it can be found in numerous East Asian religions including Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. At its essence, the mandala guides the viewer for religious meditation, but it can also be a complex microcosm of the universe.

Mandalas are very common in Tibetan Buddhism, and these types will be the examples used for this short essay. As a rule, Tibetan mandalas have to be geometric in nature - consisting of squares or circles emanating around a central area containing the deity of focus. This deity is typical:

1.The historical Buddha Shakyamuni

2. A bodhisattva (enlightened beings who chose to remain on the earth) such as Avalokiteshvara, Maitreya, or Manjushri

3. Buddhist guardians like Vajrapani, Mahakala or Paldem Lhamo

4. Historical religious gurus such as Tsongkhapa, Padmasambhava and Milarepa

There isn’t a definite text stating when the first Buddhist mandala appeared, but scholars have found pictorial suggestions of their presence as early as the 5th Century in Shanxi Province China. Actual drawn mandalas can be found in the Dunhuang caves from the 9th/10th Century in Northwest China.

Mandalas can take on many forms and sizes. They can be three-dimensional in nature from tabletop-sized bronze sculptures to massive architectural complexes like the 6th Century Boudhanath Stupa in Kathmandu Nepal.

Panorama of the Boudhanath Stupa Mandala and prayer flags in Kathmandu, Nepal. Construction of this structure began in the 6th Century and has been rebuilt numerous times. Getty Images.

In Asian art, what we are most accustomed to seeing are two-dimensional depictions of painted mandalas called thangkas. Thangkas are one of the traditional forms of Tibetan Buddhist painting, where ground mineral pigments are applied onto a cotton sheet. They can depict subjects like mandalas or individual deities and gurus.

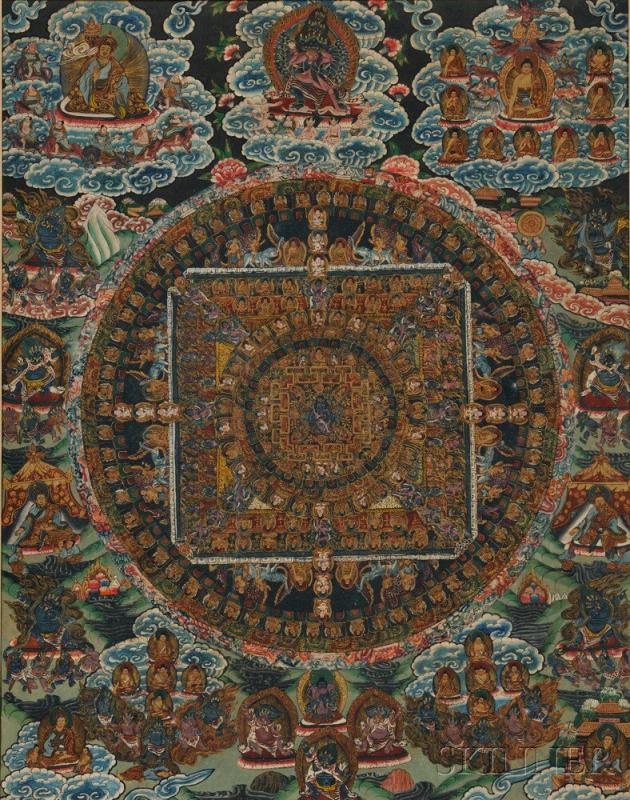

Thangkas function as an important instrument for teaching and meditation, and they can be easily rolled up when not in use. An example of an ornate thangka mandala is depicted below, sold through Skinner Auctioneers in Boston. Here we see a fierce multi-armed and multi-headed guardian with his consort as the central deity. They are surrounded by numerous Buddhas, bodhisattvas, monks and mythical beasts within an enclosed palace space.

Lot 440; Sino-Tibetan Thangka with a Mandala, 20th Century. Sold for $2,500 at Skinner, 19/20 March 2016.

A sand mandala is another type of two-dimensional mandala. Traditionally, these were made from finely crushed colored stones. The material’s weight prevented the artwork from moving with the slightest of breaths. However, this process of grinding stones became impractical and dyed sand was used as a replacement. After painstakingly drawing and filling in their designs, the monks would ceremoniously destroy their work to showcase the ephemerality of human life.

Buddhist monks making a sand mandala in Diskit gompa (monastery) at Nubra Valley, India. Getty Images.

When viewing these two-dimensional mandalas, we have to imagine that we are looking at a three-dimensional image from an aerial perspective – just like an architectural floor plan.

The mandala acts as a sacred palace for the aforementioned central deity. The walled sections protect the central deity’s inner sanctum, with doors and gateways at the cardinal directions leading to the outer sections. Throughout the mandala, we can see other landmarks including fields, temples, and even other deities and gurus. Beyond this ‘worldly’ space is the infinite cosmos.

For painted mandalas, a description of the central deity is often inscribed on the reverse, thus allowing the viewer to use the correct tantra for their meditation. The viewer can commence from the central deity and go through each outer layer (while stopping by at key figures and landmarks), or they can start from the outside, and proceed inwards. The goal is for the viewer to gain more insight to the central deity and their role in the Buddhist doctrine.

In today’s Asian art market, there is a heightened popularity with Buddhist art and painted mandalas. This category was once popular with American and Europeans interested in new age lifestyles during the 1960’s and 70’s, but nowadays, antique mandalas are acquired mostly by collectors from East Asia, particularly China.

Over the past thirty years, Chinese art collectors have been known to collect objects related to their cultural heritage including porcelain, jade carvings, scroll paintings and religious sculptures. They also have a high interest in Chinese Buddhist art, but in order to fit these works into the greater context of Buddhism, collectors would purchase objects from the Himalayan region as well including sculptures, furniture, ritual ornaments and mandalas.

In today’s market, Buddhist mandalas can go anywhere from the hundreds of dollars for 20th Century examples to the low millions for extremely rare examples from the 13th and 14th Centuries.

Lot 39; Early Tibetan Mandala of Buddha Amitabha, 15th Century. Sold for $13,915 at Leland and Little on 2/3 December 2020.

Shown here is a rare example from a 15th Century mandala depicting Amitabha Amitayus, the celestial Buddha of infinite life and light. The deity is encircled by manifestations of himself, creating a central medallion that resembles a lotus flower. They are all housed in an ornate palace with extravagant gateways. Beyond the structure is a universe inhabited with more deities and gurus.

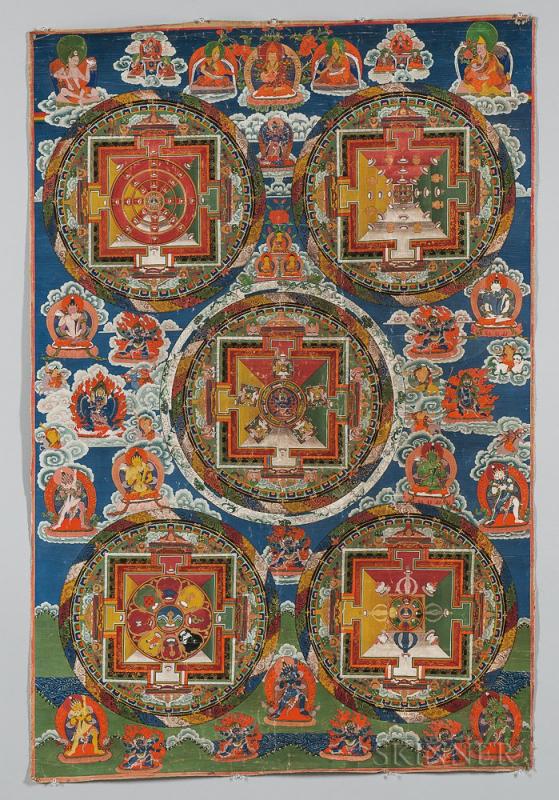

Lot 113; Thangka Depicting Five Mandalas, 18th/19th Century. Sold for $2,750 at Skinner on 16/17 March 2018.

In this example, the painting contains five mandalas, with the central scene showcasing the guardian Mahakala and his consort. The other four mandalas contain a vajra, the lightning-symbol for enlightenment, in their respective central areas. Outside of the mandalas is green earth containing numerous guardians, a middle realm containing guardians and bodhisattvas, and a celestial sky showcasing historical gurus. For the meditator, they would have to find the appropriate Buddhist tantra to navigate through this complex scene.

We hope this short blog brings some light on the characteristics and function of a mandala. Obviously, this is just the tip of the iceberg of a very difficult subject, and it would take years of studying just to grasp some of the nuances. Please check in often with Bidsquare to learn more about Asian art!

Register to bid live in upcoming online auctions on Bidsquare.

- Rafael Osona Auctions' Modern & 19th Century Design From Nantucket Estates

- Quilts as a 2025 Design Trend: A Celebration of American Heritage and Craftsmanship

- A Celebration of Sports History and Collectibles

- The Thrill of Sports Memorabilia Auctions: A Collector’s Paradise

- Demystifying Coin Condition: A Guide to the Sheldon Grading Scale

- Snoopy & Friends: A “Peanuts” Auction at Revere

- Colorful Chinese Monochromes at Millea Bros

- 12 Holiday Gifts for the “Impossible to Buy For” on Bidsquare

- Alluring Art Objects and Accessories from the Estate of Chara Schreyer

- Kimball Sterling's One-Owner Outsider and Folk Art Collection Showcases Masters of the Unconventional

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB