What is a Lithograph? Understanding the Process of Different Types of Prints

Have you ever wondered what the true difference between a lithograph and print is? Understanding the key characteristics of these different methods can be especially important if you’re looking to start collecting in the art market. The ability to recognize a lithograph can also provide a better experience when browsing museum collections and art galleries. Although, it can seem tricky at first, knowing what sets a lithograph apart from other printmaking processes is essential when considering rarity, price and technical appreciation.

Lot 13, George Bellows, Preliminaries, alternatively titled Preliminaries to the Big Bout, 1916, edition of 67 (Mason, 24). Signed "Geo. Bellows (F.B.B.)" in pencil l.r., inscribed "No 44" in pencil l.l., identified on a label from H.V. Allison & Co., Inc., New York, affixed to the backing. Lithograph on paper; Sold at Skinner for $26,250

What are the origins of lithography?

The word “lithograph” from the Greek words for “stone” and “writing” is a type of printmaking which requires a flat stone (limestone) or metal plates (aluminum or zinc.) Unlike an etching, the stone or metal plate is not physically carved into. There is no indentation or surface scratching used when developing an image in original lithography. Alois Senefelder (1771-1834) the German author who invented lithography, referred to the process as chemical printing as it is reliant on the principle that grease and water repel each other.

How is a lithograph made?

First, the design or image for the lithograph is drawn directly onto the stone slab or metal plate using an oil-based crayon or ink. This is very important to consider as it demonstrates how when prominent artists, such as Picasso or Toulouse-Lautrec, created lithographs their hand was authentically guiding the tool in an applied, original manner.

Once the design is complete, the stone is ready to be processed. A layer of powdered rosin is rubbed onto the stone, covering the image, followed by powdered talc. Then, gum arabic, or gum arabic along with a mild acid solution is brushed onto the stone in a similar manner. This is where the chemical reaction begins. The stone fixes the greasy picture that was drawn on, while the solution ensures that blank areas will absorb water and repel the printing ink.

The original drawing is then wiped down with a solvent known as lithotine, which leaves only a subtle trace of the image on the stone or meal plate. Once a layer of asphaltum is buffed onto the entire surface the stone is left to dry, creating a nice base for the ink to be applied.

To ready the stone for inking, it is dampened with water - remember, only the blank areas will absorb the water - and ink is applied to the surface with a roller. The ink, which adhered to the greasy marks left by the original drawing tool, picked up the image. Now, a moist sheet of paper is laid on top of the stone and positioned under a flatbed lithographic press. The stone or plate (with the paper on top) are covered with a board to be used as padding for the press. A pressure bar on the press is lowered to push the ink and paper as close together as possible, and, once dragged and passed through the press, a smooth application of pressure ensures that the original composition appears - thus, a lithograph is made. At first, lithographs were printed with black ink only, but soon colored ink was added and eventually mastered in the 19th and 20th centuries as a way to make artworks available to a wider audience. Keep in mind that with every layer of color, a separate stone must be made.

This highly technical and time consuming process, paired with the authenticity of the artists hand, is what makes lithographs so valuable. Oftentimes, artists would create a limited number of lithographs in a series as to control the rarity and value of a particular artwork.

Lot 134, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril, lithograph in colors, dedicated and signed in pencil [...] a alexandre HTLautrec; marked "Imp. Chaix, 20 Rue Bergere Paris," l.l. with signature and date, l.c; Sold at Grogan & Company for $75,000

How is lithography different from a print?

When looking through an lithograph auction catalog, the seller will typically detail exactly when and where a lithograph was created. This most likely means that the image was pressed using the original stone or plate. However, it’s always good to know how to spot clues on the physical paper itself that detail how the work was made.

Offset lithography vs hand-pulled. While similar, the major difference between an offset lithograph and a hand-pulled is that the original inked image from the stone or plate is transferred to a rubber blanket and then copied. Usually, the paper does not then come into direct contact with the original stone or plate. Offset lithography is used for mass-production, as the cost and time are significantly lowered. For example, offset lithography is a popular technique when making posters.

What can I look for to help me tell the difference between them?

1. Color. Do enough research to recognize the color quality of the original lithograph you are interested in. The tone and color quality of a hand-pulled and offset lithography can vary dramatically. There’s a strong chance it’s been published in a catalogue raisonné or online from a past auction.

2. Discoloration. Sometimes, if the printing press being used for an offset lithograph is not properly maintained, the aluminum plates can leave behind unflattering blemishes or oxidation in the blank areas of the image.

3. Magnification. Don’t be shy, bring your magnifying glass. Marks from a hand-pulled lithograph will show a random dot pattern created by the tooth of the original surface. The multiple color layers will show up slightly overlapping with a very saturated look. However, prints from an offset press will have a more mechanical dot pattern from the color separations and appear in perfect, neat rows - as a piece of machinery would only be able to create.

4. Signature. As with any original artwork, the artist would have signed their lithograph. However, mass-produced versions may be lacking this ever important finishing touch.

5. Thickness. Without compromising the artwork, lightly feel the thickness of the ink. If the ink is slightly raised, there’s a better chance you are looking at an original lithograph, whereas, an offset lithograph will result in flat ink application.

Lot 733, Wayne Thiebaud, Paint Cans, 1990, Lithograph in colors on Arches paper (framed) Signed, dated and numbered 78/100, 32" x 25" (sight) Printer: Trillium Graphics, Burbank, California, Publisher: Chicago Art Expo, Chicago, Provenance: Private Collection; Sold at Rago for $26,250

How many types of lithographs are there?

Since the 18th century, when Alois Senefelder invented the original method, there have been many advances in the field of printmaking and lithography. High volume printing presses made for posters, maps, books, newspapers, packaging, etc., all have their own specific techniques. However, in the art market you are most likely to encounter:

1. The oldest lithography technique: Original stone lithographs, where an oil-stick or ink is used to create an image on a heavy stone to be directly printed on paper using a series of chemical reactions.

2. Similar to a stone lithograph: An original plate lithograph uses an aluminum plate (cheaper and more transportable than stone) to be directly printed on paper.

3. The mylar method: The artist draws on mylar, which looks like a plastic sheet or polyester film. Then, when ready, the artist transfers the image onto the lithographic plate and prints it on paper.

4. Reproductions of an original: A photograph is taken of an original artwork, whether it be a painting, drawing, or lithograph, which is transferred to a lithographic plate to be printed on paper.

5. Using an offset press: The original print is transferred to a rubber blanket to be run through a printing press and used hundreds of times. The original stone or aluminum plate is no longer needed.

Now that we’ve walked you through the basics of what a lithograph is, we hope this allows you to begin distinguishing how a particular artwork was made and why it matters. Consider asking yourself, how many years between the original and the reproduction there are or what pieces of machinery were put between the artist's hand and the print in front of you. When you look to buy a print or, perhaps, an original lithograph - straight from the stone, you’ll feel better now that you certainly understand the difference.

Browse all past and upcoming Posters & Prints Auctions so you can register to bid and view previous auction results on Bidsquare.

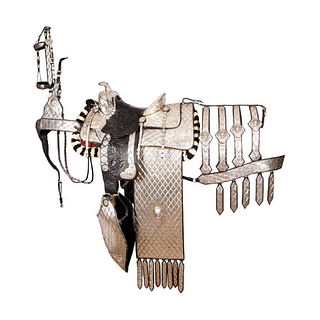

- Rafael Osona Auctions' Modern & 19th Century Design From Nantucket Estates

- Quilts as a 2025 Design Trend: A Celebration of American Heritage and Craftsmanship

- A Celebration of Sports History and Collectibles

- The Thrill of Sports Memorabilia Auctions: A Collector’s Paradise

- Demystifying Coin Condition: A Guide to the Sheldon Grading Scale

- Snoopy & Friends: A “Peanuts” Auction at Revere

- Colorful Chinese Monochromes at Millea Bros

- 12 Holiday Gifts for the “Impossible to Buy For” on Bidsquare

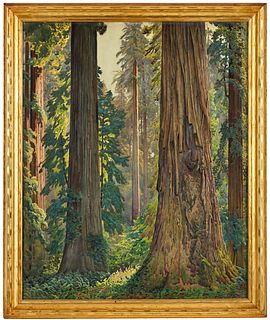

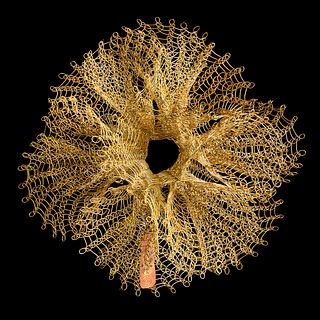

- Alluring Art Objects and Accessories from the Estate of Chara Schreyer

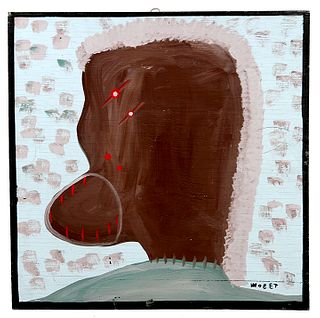

- Kimball Sterling's One-Owner Outsider and Folk Art Collection Showcases Masters of the Unconventional

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB