The Lasting Impressions of Japanese Block Prints

The history of the Japanese block prints traces back to 764 when the Empress Kōken commissioned small scrolls of woodblock print. These contained the Buddhist text and were circulated to temples across Japan. Circa 1570 – 1640, a designer-painter, Tawaraya Sōtatsu was known for using wood stamps to print on silk and paper. However, until the eighteenth century, woodblock printing was only a method of reproducing texts. The advent of Edo period changed it all.

Lot 387, Japanese, Ukiyo-e color woodblock prints, collection of three, 19th century | Rago

Ukiyo-e – Pictures from the Pleasure Districts of Japan

Edo is the erstwhile name of Tokyo, before it was made the capital of Japan. The Edo period holds a place of extraordinary significance in the bygone era. Tokugawa Ieyasu and his descendants emerged as the unchallenged rulers during this era. From 1603 – 1867, it was the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and 300 regional daimyo that led the country. The 250 years of their rule were marked by outstanding economic growth, punitively controlled social hierarchy and conservative foreign relation policies. Interestingly, it was also the period of creative prosperity. The merchants and artisans, who were at the lowest social strata of the Confucian hierarchy, were the ones who enjoyed the maximum pleasures of an economically prosperous society. They patronized geisha and courtesans culture and kabuki theatre.

An art form practiced in Edo period particularly stands out for making an indelible impact on the cultural tapestry of Japan -- Ukiyo-e woodblock printing. Ukiyo-e literary translates to "pictures of the floating world". Proliferating during 17 - 19th centuries, Ukiyo came to be associated with hedonistic lifestyles and sensual pleasures of the merchant class.

Woodblock print became the face of Japanese art in the West, especially in later part of 19th century. Landscape works of Hiroshige and Hokusai generated great interest among art collectors and Impressionists such as Édouard Manet, Claude Monet and Edgar Degas. It also influenced Post-Impressionists and Art Nouveau artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Slightly similar to the western woodcut printmaking, the Ukiyo-e technique is noteworthy for its unmatched color blending and graduation effects that no machine could replicate. What differentiates it from the western woodcut is the use of water-based inks unlike the former which employs oil-based ones. The water-based colors lent a brightly glazed sheen and transparency to the print.

The five main genres in Japanese block prints are beautiful women, kabuki theatre actors and scenes, landscapes, birds and flowers, and historical events, including wars and samurai. Other popular subjects included erotica, tea ceremony, folk tales and travel scenes.

Skillful Division of Labor

The publication of Ukiyo-e is an apt example of the division of labor in the ancient Japanese society. In fact, it was very rare to find artists cutting and carving their own woodblocks. The process always involved artisans at four different levels: publisher/producer, artist, carver, and printer. Hanmoto or the publisher was responsible for the entire printing process right from beginning to end. He would survey the market; decide on a subject matter; hire a designer; and supervise, produce and distribute the prints.

The process began with the publisher commissioning an artist for print after arriving on a subject matter. The selected artist then sketched a composition using black ink on a thin sheet of paper. Thereafter, the sheet was sent for printing. The printer would paste the sheet with the drawing facing down on a smoothened cherrywood block. Oil was applied so the outlines stood out prominently. The paper was pulled away with a thin trace left behind along with the visible outlines of the design. This helped the engraver cut and carve the wood following the lines, which was indeed a master skill. The block face was then brushed with black sumi ink. A damp sheet of paper was rubbed rigorously on the block with a twisted cord, which was covered with bamboo sheath. The design was sent to a government censor, who would review the sketch for any religiously immoral or politically subversive material.

After the censor approval, it was sent for coloring to the artist. Using this proof, the engraver would carve multiple blocks, i.e. one block for every color with the kento’s registration marks. And that’s how the design was made ready for final printing and circulation.

Notable Master Artists & their Contribution to Japanese Block Printing

In the earliest Ukiyo-e block art, only black-and-white prints were produced and use of color was limited. Hishikawa Moronobu was one of the leading monochrome print artists, whose image of attractive women made waves. Color prints started appearing gradually. In the beginning, it was either hand coloring or occasionally up to two hued ink blocks were used. In 1740s, Okumura Masanobu was one of the foremost artists to have worked with multiple woodblocks to print color in a modest fashion. Two decades later, with Suzuki Harunobu inventing Nishiki-e technique, "brocade prints" took off in a big way. Now full-color production with more than 10 blocks was here to stay. Brocade printing is a technique of using separate woodblock for each color in a step-by-step method. Another innovator in this regard was Kinroku, an engraver, who made it possible to fit the different blocks of separate colors on the page to create a single image.

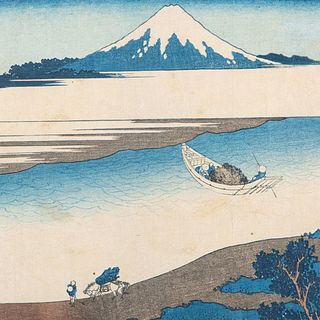

Lot 313, Katsushika Hokusai, The Jewel River in Musashi Province, Woodblock | Cowan's Auctions

Torii Kiyonaga was a noteworthy ukiyo-e artist belonging to the Torii school. He was born Sekiguchi Shinsuke to a bookseller in Edo. Kiyonaga was not biologically connected to the famed Torii family but became the head of the Torii group after his teacher and adoptive father Torii Kiyomitsu’s death. Before joining Torii school, he received training under Suzuki Harunobu, Isoda Koryūsai, and Kitao Shigemasa, who greatly influenced his prints. One of the key highlights of his works was the images of beautiful women. Interestingly, the women in his prints were tall, full-bodied unlike the depictions of his predecessors who portrayed slimmer and younger women. This can be attributed to both his personal style and the use of larger-sized papers.

Kitagawa Utamaro is another well-known ukiyo-e figure. In the 1790s, he created renowned Bijin ōkubi-e works or pictures of pretty women with large head. Master artist Tōshūsai Sharaku is famed for the portraits of kabuki actors. Sharaku’s portrait compositions highlighted a sense of realism that was quite rare in the prints of the age. Hokusai is also a significant name revered for his famous woodblock print series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. It comprises the internationally-acclaimed The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

A Low-down on Collecting Woodblock Art

It makes sense to do a reasonable amount of research about this art form, its history and the famous artists before making a purchase. As a beginner, you may want to start off by buying 20th century “re-prints”, which are available at more attractive prices compared with the original works of Japanese masters. Collectors would be astonished to find the woodblock re-prints have a fine quality similar to the originals. Some of the 20th century prints include titles in English and/or artist signatures in English phonetic translations. This helps the international buyers get a better understanding of the Japanese art and artists in order to make an informed choice.

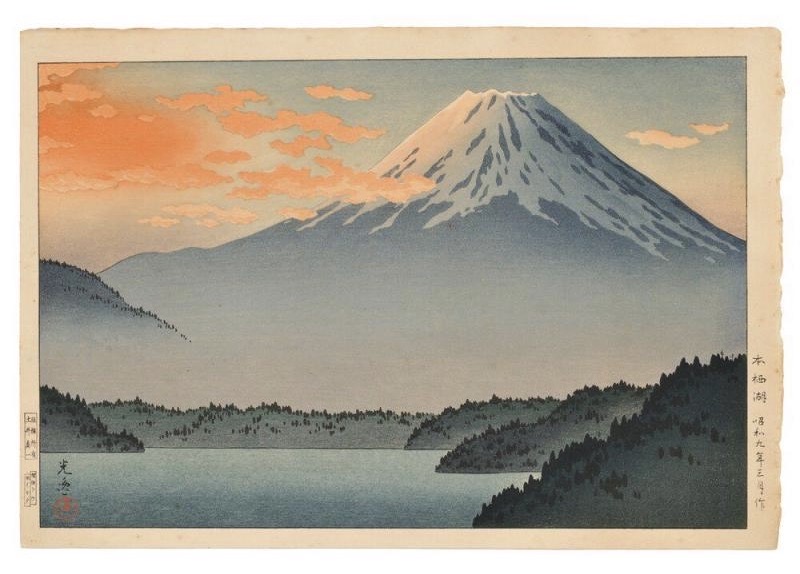

Lot 113, Tsuchiya Koitsu (1870-1949), Motosu Lake, Japan, March 1934, color woodblock print, published by Doi Sadaichi | Skinner

The best way to scrutinize the artwork is to look at an unframed print, preferably with a magnifying glass. Prints mostly have some ink bleed visible on the reverse side, something that the reproductions do not. Besides, you can spot paper fibers in original woodblock prints, whereas reprinted copies have a smooth texture. Deciphering the name of a publisher and date can be a major game changer. Some of the modern Japanese publishers who produced standardized quality re-prints include Doi, Watanabe, Adachi and Uchida.

Finding authentic original prints at ideal prices is every ukiyo-e art collector’s dream. Nevertheless, price-conscious collectors can always look for budget options. These include the design series of major Japanese masters available in fairly good quality re-prints at competitive prices.

- Rafael Osona Auctions' Modern & 19th Century Design From Nantucket Estates

- Quilts as a 2025 Design Trend: A Celebration of American Heritage and Craftsmanship

- A Celebration of Sports History and Collectibles

- The Thrill of Sports Memorabilia Auctions: A Collector’s Paradise

- Demystifying Coin Condition: A Guide to the Sheldon Grading Scale

- Snoopy & Friends: A “Peanuts” Auction at Revere

- Colorful Chinese Monochromes at Millea Bros

- 12 Holiday Gifts for the “Impossible to Buy For” on Bidsquare

- Alluring Art Objects and Accessories from the Estate of Chara Schreyer

- Kimball Sterling's One-Owner Outsider and Folk Art Collection Showcases Masters of the Unconventional

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB.jpg)

.jpeg)