In Appreciation of Toshiko Takaezu, Japanese-American Ceramic Artist, Mother of Moon Pots: AAPI Heritage Month

Bidsquare is proud to celebrate AAPI Heritage Month:

Asian American and Pacific Islanders or (AAPI) are an integral part of the American cultural mosaic, representing over 23 million people and encompassing approximately 50 ethnic groups and over 100 spoken languages, with connections to Chinese, Indian, Japanese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, Hawaiian, and other Asian and Pacific Islander ancestries. What initially started as a commemorative week, the first ten days of May, was expanded by Congress in 1992 to encompass a month long celebration (AAPI Heritage Month) to recognize the emigration of the first Japanese Americans on May 7, 1843, and to honor the Chinese Americans who contributed to the transcontinental railroad which was completed on May 10, 1896. Now, the month of May is dedicated to the recognition of all AAPI and represents the rich heritage and unique traditions of millions of Americans.

As the uptick in race-based violence against AAPI continues to rise since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is more important than ever to shine a light on the historical achievements and contributions that generations of AAPI have had on the fabric of American culture and society. One such story is that of Japanese-American artist, Toshiko Takaezu, and her lifelong yearning to express the mysterious totality of nature through clay.

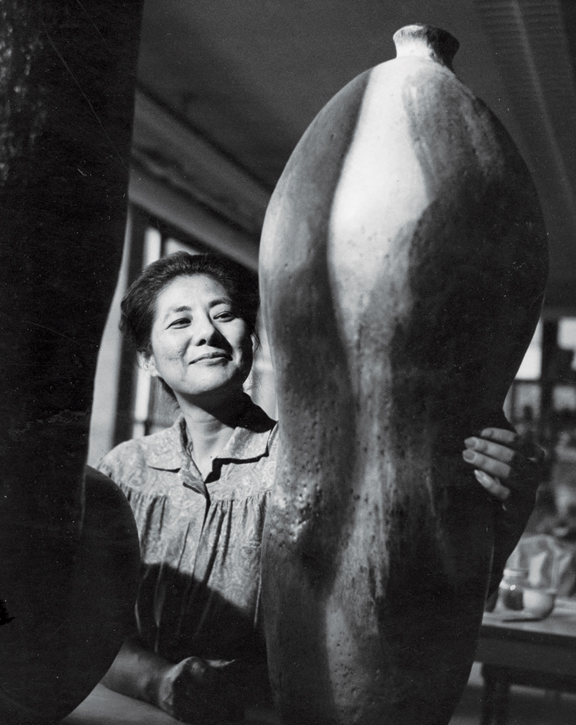

Toshiko Takaezu, Photo: John Paul Miller, ca. 1960s; Courtesy American Craft Council

Toshiko Takaezu, Mother of Moon Pots

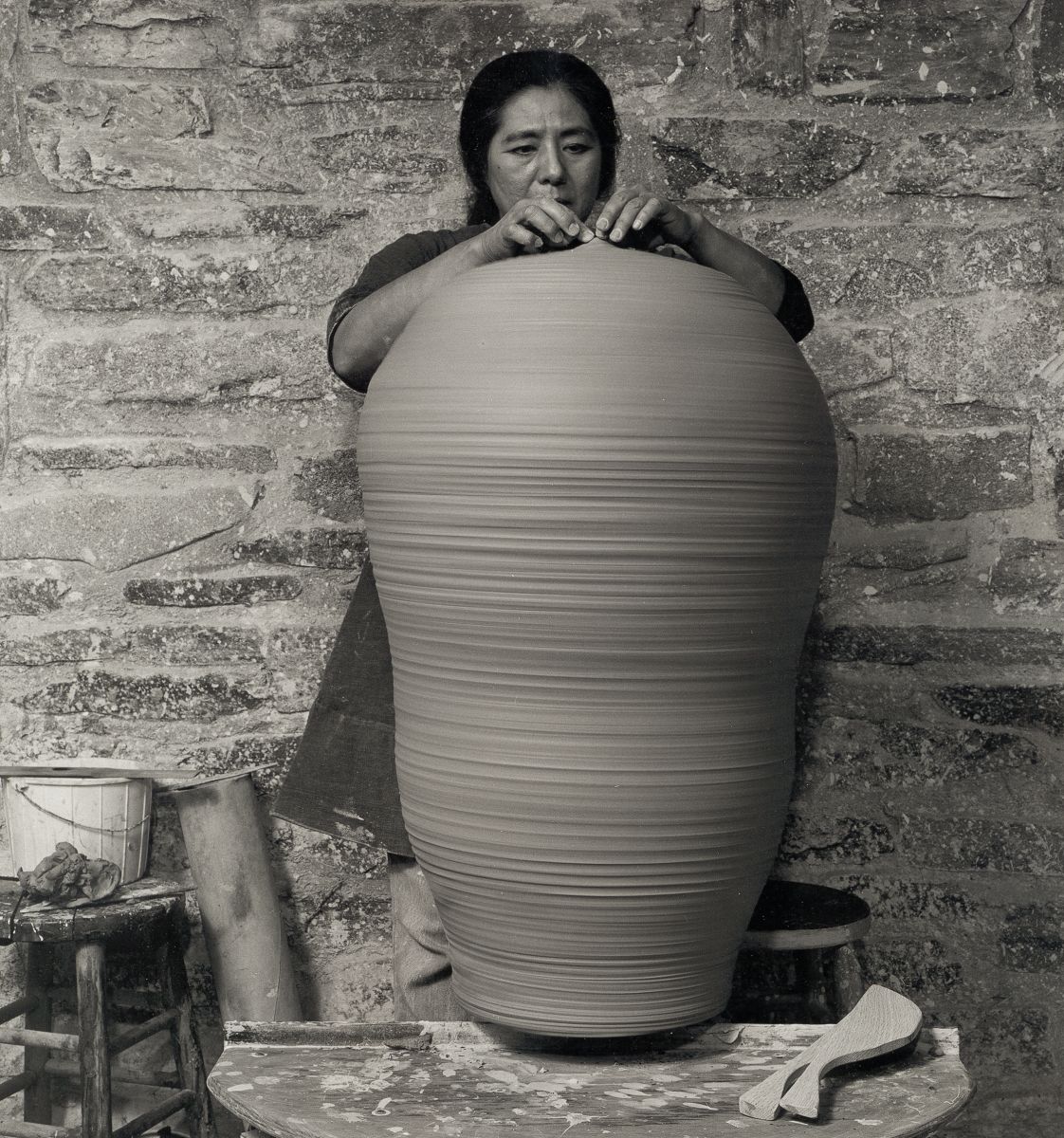

American artist Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011) was born in Pepeekeo, Hawaii to Japanese immigrant parents - the middle of eleven children. Her traditional Japanese upbringing and natural surroundings would come to deeply inform her artistic values and connectivity to what would become a decades long career in the ceramic arts. Her torpedo-like, hollow bodied forms, known as Moon Pots or Moon Balls - some with a “rattling” ability due to the inclusion of small beads - would become a trademark symbol of Takaezu’s poetic contributions to the cannon of clay history. Some works, small enough to fit in the palm of your hand, and others, massive standing sculptures resembling a vertical pod of sleeping whales, are thought of as crowning achievements in clay. Takaezu also excelled in bronze casting, weaving and painting. Toshiko Takaezu and her ceramic work holds a significant place in the post-World War II craft movement in the United States, especially as a female artist of Japanese heritage. Her aesthetic blended both her Western and Japanese cultures and to this day remains an essential demonstration of ceramics as fine art and craft - a discussion she both avoided and quietly dominated.

Toshiko Takaezu, Ocean Edge Closed Form, USA, c. 1990, glazed porcelain | Rago

Toshiko Takaezu, Small Moon Closed Form (with rattle), USA, c.1985, glazed stoneware | Rago

Teaching and Self-Discovery

Throughout her career and into her later years, Takaezu would make a lasting impression on her students as a teaching artist. She maintained a reputation for kindness as well as toughness and ingrained zen-like clay philosophies into her methods such as the practice of “saving nothing” as a means to create more freely. She was often heard repeating the mantra, “no ashtrays, no souvenirs” insisting on the higher calling that ceramicists had to offer. Her first teaching experiences in 1948, at YWCA in Honolulu would inspire her to further her own clay education and lead her to enroll at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. In 1951, she left her island home for the first time for Cranbrook and would eventually overcome shyness and intimidation upon meeting her instructor, Finnish pottery master Maija Groell, a pivotal influence and mentor for Takaezu. Takaezu says of Groell, “[she was] an unusual and rare human being who felt it was important for students to become individuals. It was through her criticism that I began to discover who I was.”

Takaezu would eventually become Groell’s assistant at Cranbrook, which led her to teach summer sessions in 1954, 1955, and 1956. She would then move on to hold a full-time teaching position from 1956-1964 at the Cleveland Institute of Art and later transition out to join the faculty of the Visual Arts Department at Princeton University from 1966 until 1992. She also held workshops throughout the country and invited apprentices to participate in the making of her pieces in her at-home studio. Her fascination with growing vegetables was equally as important to Takaezu as were her pots; live-in apprentices mirrored her holistic lifestyle, joining her for morning yoga, gardening, loading and unloading the kiln and cleaning the studio.

Takaezu allowed her work to slowly evolve as part of her "don't plan" clay mentality, drawing comparisons to the systematic nature that occurred within her vegetable garden. She lifted her works out of the kiln with the same admiration and wholesomeness as she did when digging potatoes out of soil. She reflected on her repetitive process, where her quest for the "perfect" piece served as both motivation and a feared detractor, "..there is all these unknown things about the firing which makes it fascinating and intriguing and that keeps you going," she adds, "...and I'm sure that I've gotten some that's perfect and yet I don't want to admit that or I would stop - and what is perfection?"

A Journey to Okinawa

In the fall of 1955, Toshiko Takaezu and her family members would embark on a month-long trip to the Okinawa Prefecture and other parts of Japan in an effort to understand more about her heritage. Together they visited religious centers and spent time in a Zen Buddhist temple where they studied the tea ceremony. They sought out folk potteries to which Takaezu would meet and develop friendships with Japanese master potters Kitaoji Rosanjin, Shōji Hamada, and Toyo Kaneshige.

Ceramic artist Toshiko Takaezu working on a thrown vessel

The Work & Unsaid Qualities

Takaezu developed memorable forms which would only be compared in scale and energetic abundance to iconic American ceramic artist Peter Voulkos. Although much less aggressive in technique and design, Takaezu’s work was taken just as seriously as her contemporary and remains, to this day, giant demonstrations of the medium in terms of scale and glaze application. Many of her glazes, poured, brushed and dipped at random, would develop streaks and melting lines - evoke dramatic sunrises and panoramic landscapes. As for the physical, painterly glaze application, Takaezu valued her privacy while making these various choices. She saw the act of glazing as a very personal dance and was known for expressing her preference to be alone with her pots during the process.

As cited in the biographical book, In the Language of Silence, The Art of Toshiko Takaezu by Peter Held, Takaezu’s work can be characterized by a number of contrasts which expand the impact of her work: subtlety and vividness, monumentality and intimacy, as well as modern and entirely ancient. It’s also vital to understand that the presumption that her work is entirely influenced by Japanese art is to ignore her development as an American female artist, “...it’s important not to exoticse her work. She should be recognized as an individual and original creator; the product of varied influences and her own distinctive ideas.” That isn’t to say that being part of the AAPI diaspora was lost on Takaezu. She specifically noted that her influences came much more from Japanese culture in general, opposed to Japanese ceramics directly. Perhaps, the most appropriate parallel between her work and heritage were her inclinations, “...one can’t help but associate her laconic discussion of her work with the Japanese belief that the most profound things cannot be spoken.”

Supporting a Legacy

Toshiko Takaezu died at the age of 88 on March 9, 2011 in Honolulu, following a stroke she suffered in 2010. In response to her passing, The Toshiko Takaezu Foundation was established in 2015 to support her legacy. Her work was the subject of a traveling retrospective that originated at the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto in 1995 and the exhibition “The Poetry of Clay: The Art of Toshiko Takaezu” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2004. Her work has been exhibited and collected by museums and universities across the country including: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Princeton University, The Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, RISD, the Seattle Art Museum, Honolulu Museum of Art, and dozens of other prestigious institutions.

_______________________________

References:

The New York Times, Toshiko Takaezu, Ceramic Artist, Dies at 88, William Grimes

In the Language of Silence, The Art of Toshiko Takaezu by Peter Held

www.toshikotakaezufoundation.org

The new Bidsquare mobile app is available to download for free in the Apple Store and Google Play. Download it today to bid on the best fine art and antiques.

_______________________________

With new auctions added daily, we're always ripe for the picking. Be sure to check Bidsquare's monthly finds for little bits of wonderful from every catalog.

Don't have a Bidsquare account? Sign up here!

Be in the know about upcoming auctions and exciting post-sale results by following us on Facebook and Instagram.

_______________________________

Jessica Helen Weinberg | Senior Content Editor at Bidsquare

- Quilts as a 2025 Design Trend: A Celebration of American Heritage and Craftsmanship

- A Celebration of Sports History and Collectibles

- Antiques and the Arts Weekly Q&A: Allis Ghim

- The Thrill of Sports Memorabilia Auctions: A Collector’s Paradise

- Demystifying Coin Condition: A Guide to the Sheldon Grading Scale

- Snoopy & Friends: A “Peanuts” Auction at Revere

- Colorful Chinese Monochromes at Millea Bros

- 12 Holiday Gifts for the “Impossible to Buy For” on Bidsquare

- Alluring Art Objects and Accessories from the Estate of Chara Schreyer

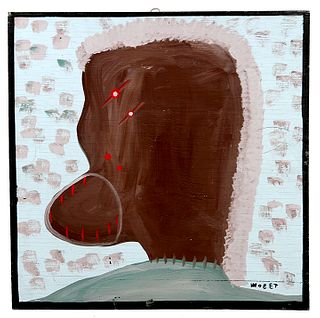

- Kimball Sterling's One-Owner Outsider and Folk Art Collection Showcases Masters of the Unconventional

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB