Around the World with the Allan Stone Collection

On October 19th, Tribal Art from the Collection of Allan Stone and Other Owners goes to auction at Rago, bringing together over 200 lots of ethnographic property from around the world including art and artefacts of African, Oceanic, American and Asian origin. Ahead of this exceptional and culturally fascinating auction, we invite you to join us on a globe-trotting look at some of the highlights of the sale.

And don’t worry; no passport required!

African Art

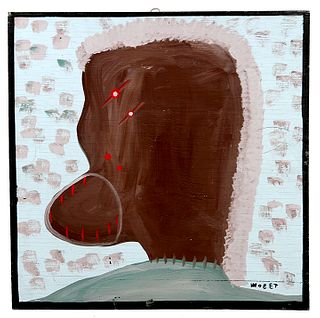

Lot 96, Luba-Songye, Kifwebe Mask, Congo; Estimate: $100,000 - $150,000

The striated face masks known as kifwebe likely originated in what is now the Shaba region of the Democratic Republic of Congo, southeast of the Congo River basin, an area inhabited by both Songye and Luba groups. For this reason, it is not unusual to see a masking tradition that seems to incorporate stylistic elements of both groups. This mask belongs to a small corpus of Luba-Songye masks generally known as being in the 'Mussolini style'. About a dozen masks of the Mussolini workshop are known.

This example is characterized by a box-like projecting mouth, prominent semi-circular bulbous upper eyelids, the broad triangular nose, and large dominant forehead accentuated with a band extending from the nose across the top of the head. Hierarchical and functional distinctions between female and male masks are reflected in color and in sculptural features. Though this is a female kifwebe mask, the dark color is typically seen in male masks.

As documented by anthropologists, the precise functions and roles of these masks have evolved over time, reflecting their complexities and importance within the society. The traditional political organization of the Songye rested on the authority of the chief. In consolidating and bolstering the strength of their rule, chiefs were assisted by two secret men's associations, one practicing witchcraft (buci) and sorcery (masende), and the other, bwadi bwa kifwebe, who were responsible for the performances of the kifwebe masks. Bwadi bwa kifwebe assured the well-being and continuity of the community by enforcing societal laws and appealing to benevolent spirits. This society possessed the power of political and social control, demanded contributions from spectators during its public appearances and could also lease its services to other associations, such as initiation ceremonies.

Lot 115, Bamileke Style, Bush Cow Mask, Cameroon; Estimate: $3,000 - $5,000

The Cameroon grassfield kingdoms were organized under a king (fon) and a group of titled nobles, essentially as a hereditary aristocracy. The display and ownership of masks were important indicators of lineage, privilege and prestige. Masks carried symbolically potent imagery, whether transmitted through zoomorphic and anthropomorphic forms or through adornment with costly and prestigious materials such as beads, cowrie shells, or brass. The bush cow (short horn buffalo) represents cunning, bravery and exceptional physical strength. Hunters made a gift of the heads to their king; bush cow skulls were hung over doorways and their horns were made into prestige drinking vessels. This bush cow mask is elegant and strongly sculptural, a good example of how these masks evolved stylistically in the 20th century.

Oceanic Art

Lot 147, Female Ancestor Figure, Fiji; Estimate $100,000 - $150,000

Ancestor figures were physical representations of the dead which could be occupied by their spirits from time to time. They lived in the spirit houses set aside for the dead in Fijian villages. There appear to be two basic types: those intended to stand up, with feet, a base or pegs, and those incorporated into hooks used for suspending offerings. Of the extant corpus, female figures considerably outnumber male examples.

James Hooper, who probably acquired this figure sometime between 1952 and 1963, is one of the foremost collectors of ethnographic art. Fascinated from childhood by indigenous people and their customs, he amassed an exemplary collection of ethnographic objects which has been described as the last of the great British collections of art from Africa, Oceania and the Americas. Hooper was primarily interested in Polynesian art, but his collection also encompassed art from Melanesia and Micronesia, and finally African and Native American art.

This figure was one of a pair of male and female figures sold at the Hooper auction at Christies on 19 June, 1979 and acquired by James Willis who subsequently sold it in 1989 to Allan Stone. Experts in the field date this figure from the early to mid-19th century, prior to Fijian conversions to Christianity.

Lot 157, Mendi, Shoulder Shield (Elayaboor), Papua New Guinea; Estimate $1,500 - $2,500

Most battles in Melanesia were fought with projectiles (spears, throwing clubs, stones and, more recently, the bow and arrow). Shields were the primary defense against these weapons and were often adorned with powerful motifs, color, and symbols to protect the carrier from magic or impart fear in an opponent. Melanesians made cover or parrying shields for use on the move: either rectangular plates of bark (shomo) or wooden shields. Wooden shields came in two forms: oval shields, called wörumbi, and eláyaborr, characterized by a wide notch at the top that the wearer would put his arm through, thereby keeping the shield close to his body. Melanesians also made standing shields, such as lot 144, thought to have been used in protecting villages or as stationary cover after a battle has commenced.

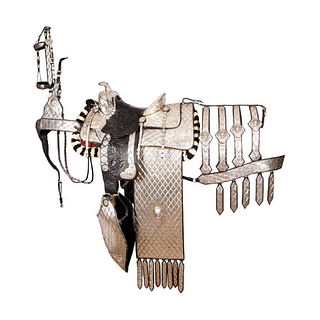

American Art

Lot 186, Sioux, Beaded Cradleboard, Great Paints (N.A.); Estimate: $4,000 - $6,000

Cradleboards are a type of protective baby carrier, historically used by the indigenous peoples of North and Central America. They enabled a mother to carry her child on her back, strap it to the side of a horse, or lean it against a tree or building when busy. The stiff wooden baseboard protected the baby's spine in its first few months of life, whilst the hood provided shade from the sun or shelter from wind and rain. Many elders believed cradleboards 'socialized' infants when worn because it brought the child to the eye level of the adults. This example was made by a member of the Sioux, a confederation of seven related tribes of the Great Plains region of North America. It is made of both animal skin, stitched with sinew, and covered in colorful beadwork in geometrical designs on a white background.

Lot 253, Kiowa, Ledger Drawing, Great Plains; Estimate $2,000 - $3,000

Ledger drawings are so-called because of the paper on which they were drawn, typically from account books. As a genre, ledger drawing is a continuation of traditional pictorial art originally painted on buffalo hide robes and tipi covers recording battles, heroic deeds, ceremonies and everyday customs of Plains Indians as their way of life passed into history. In contrast to the traditional hide paintings, however, much of the ledger art was executed by artists held on reservations or in prison in the last third of the 19th century, using the tools and materials of a foreign culture—crayons, pencils, and paper. When young Plains warriors learned to draw in this new style, the pictures they made were incorporated into the war-honors system of Plains life. The men memorialized their deeds in pictures that they utilized in the oral recollections of their bravery and battle, victory and loss. Some of the best-known ledger art was created at Fort Marion in Saint Augustine, Florida where seventy-two Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho and Caddo men were imprisoned between 1875 and 1878. Encouraged to draw by their military captors, twenty-six of the prisoners, mostly Cheyenne and Kiowa, produced hundreds of drawings and a number of books detailing their former lives, as well as their new lives as prisoners and students.

Asian Art

Lot 197, Toraka, Zoomorphic Sarcophagus (Erong) Celebes; Estimate $10,000 - $15,000

The Toraja of Indonesia bury their dead according to status within the community. Boat shaped coffins are reserved for the elite while the middle rank and lower rank have buffalo and pig shaped sarcaophagi, respectively. Depending on the status of the deceased, the funerals require extensive planning and, in some cases, days to complete. Funerals serve as arenas for exchange and are also occasions for the confirmation in death of the rank and role of the deceased and his or her close kinsmen.

Lot 209, Shiva Sculpture. South India; Estimate $800 - $1,200

To his devotees, the god Shiva is the supreme god. He is existence itself. He cannot be limited. He is the indefinable absolute. Because Shiva is all things, both the beginning and the end, he is responsible for both creation and destruction, as it is understood that these two activities go hand in hand, that one cannot exist without the other. In the Hindu trimurti (the concept of a trinity of gods), Shiva's role as the god of destruction is emphasized, and he is often thus referred to as the Destroyer. Shiva has both male and female components within his being. The divine female part of his essence (his shakti) provides him with creative energy. His shakti is usually understood to manifest in the form of a goddess who is regarded as his consort; Parvati is one of her many names. In his dual role as creator and destroyer, Shiva performs a cosmic dance, representing the continual cyclical nature of the universe, and when he does so he is called Nataraja. Not always actively engaged in the affairs of the world, Shiva spends much of his time as a meditating ascetic, living high in the Himalayas on Mount Kailasa.

Don't have a Bidsquare account? Sign up here!

Be in the know about upcoming auctions and exciting post-sale results by following us on Facebook and Instagram.

- Rafael Osona Auctions' Modern & 19th Century Design From Nantucket Estates

- Quilts as a 2025 Design Trend: A Celebration of American Heritage and Craftsmanship

- A Celebration of Sports History and Collectibles

- The Thrill of Sports Memorabilia Auctions: A Collector’s Paradise

- Demystifying Coin Condition: A Guide to the Sheldon Grading Scale

- Snoopy & Friends: A “Peanuts” Auction at Revere

- Colorful Chinese Monochromes at Millea Bros

- 12 Holiday Gifts for the “Impossible to Buy For” on Bidsquare

- Alluring Art Objects and Accessories from the Estate of Chara Schreyer

- Kimball Sterling's One-Owner Outsider and Folk Art Collection Showcases Masters of the Unconventional

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB