A Horse, or Two, in This Race

When the Spartan army took home the horses of Xerxes as spoils of war in 479 BCE, after the battle of Plataea, it began a movement of eastern horses to Europe that was to last throughout the period of classical antiquity. Horses were a specialty in Persia. Darius the Great (551-486 BCE) had vastly expanded the Achaemenid Empire and set up imperial stud farms to supply his army. Herodotus immortalized the Nisaean name, celebrating their magnificence and swiftness. Centuries later, the Romans imported horses for chariot racing to outposts of Empire as remote as Britannia, favoring the Nisaean horse of Persia, the Spanish horse, and the North African barb.

Fast-forward over a millennia, and the eastern horse is still a symbol of royalty and empire. Henry VIII (1491-1547) is recorded setting up a royal stud farm to acquire and breed essentially the same horses: Spanish, North African barb, Egyptian and Arabian, and “all other Eastern horses.” In 1605 King James I established Newmarket as a center for racing and imported the Markham Arabian in 1616. The Markham was greatly admired and inspired widespread desire for eastern horses, but it was the Restoration and the rule of racing-obsessed Charles II in 1660 (see lot #784) during which the import of eastern horses for the improvement of racing and riding stock dramatically increased. Beyond the diplomatic gift or battles of the Ottoman wars, the main conduit for the horses was through the Levant Company, which held the trade charter for Britain in the Ottoman Empire. Beginning in 1582, its trade was mainly cloth and spices. With the rise in popularity of horse racing and wagering in Britain it was not long before horses were requested. Obtaining horses was no easy task for the Turkey merchants. The Ottoman Empire dwarfed Britain in all aspects of size, wealth, sophistication, and splendor. Their horses were appropriately magnificent. Pampered and pedigreed, they were treasured and not easily parted with.

According to Donna Landry (Noble Brutes, How Eastern Horses Transformed English Culture, Johns Hopkins, 2009), over the period 1650-1750, British merchants managed to acquire roughly 200 horses. Exported from the main Levant Company trading centers in Constantinople, Aleppo, Alexandria, and Smyrna, the British called the horses either after their port, or the catch-all appellation, “Arabian”. A number of these horses earned fame in Britain, with three of them credited as foundation stallions for the English Thoroughbred breed. The eastern emphasis on the importance of pedigree made perfect sense to the English aristocracy, all of whom claimed descent from King Alfred (848-899). A mania for breeding and racing purebred “Arabians” gripped the country. Of the three foundation stallions, the Byerley Turk reached England in 1689, the Darley Arabian in 1704, and the Godolphin Arabian in 1724. The British crossed Turkic, Barbary, and Arabian bloodlines, sometimes with domestic horses, selectively breeding for speed, and, adding richer fodder than obtainable in the desert, a superhorse emerged. As the British Empire began to take shape, beginning a maritime expansion, establishing colonies, and becoming a greater trading power, so the Thoroughbred took shape, adopted as a British creation and symbol of Empire. In 1791, the Jockey Club required registry for all racehorses, and the Thoroughbred studbook effectively closed to outside additions.

Explorations in DNA analysis have confirmed 95% of all Thoroughbreds can be traced through their paternal sire line to the Darley Arabian [Bower, M.A. et al. The genetic origin and history of speed in the Thoroughbred racehorse. Nat. Commun. 3:643 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1644 (2012)].

Analysis of male-specific Y chromosomes has further indicated that the Darley Arabian was actually of Turkoman origin, not Arabian [Cunningham, E. P., Dooley, J. J., Splan, R. K. & Bradley, D. G. Microsatellite diversity, pedigree relatedness and the contributions of founder lineages to thoroughbred horses. Anim. Genet. 32, 360–364 (2001)].

Which brings us to our paintings coming up for auction at Pook & Pook on April 21st and 22nd.

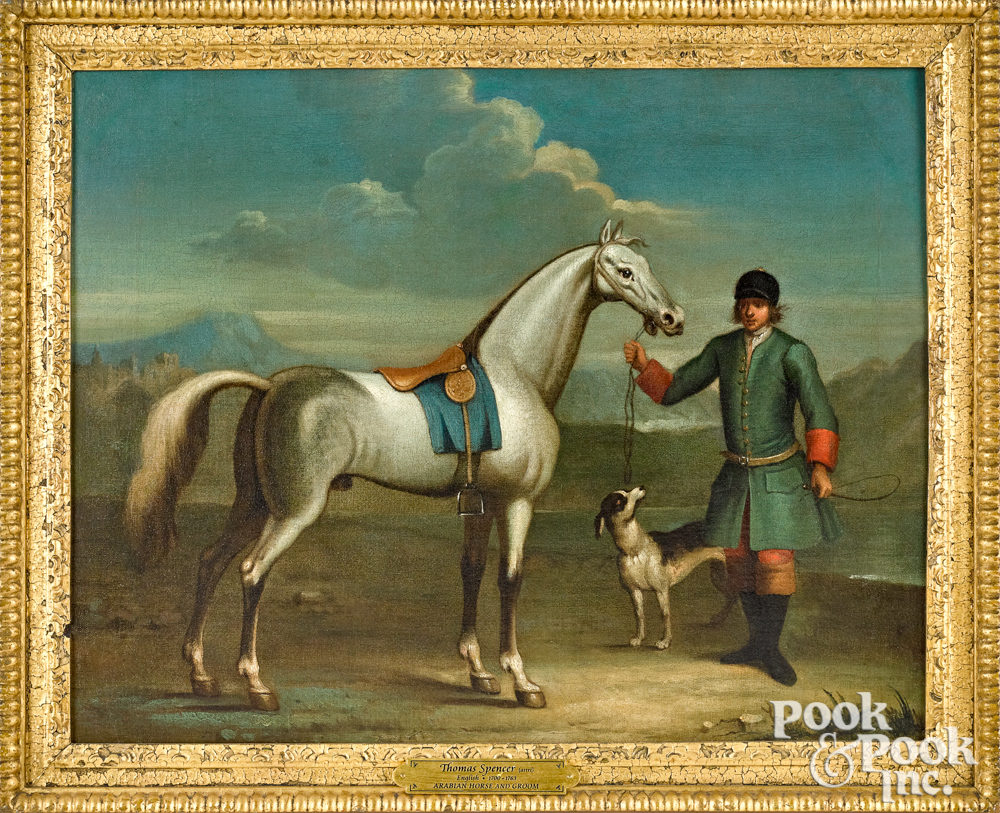

Lot 71, School of Thomas Spencer (British 1700-1763), oil on canvas of an Arabian horse and groom

Lot 71, School of Thomas Spencer (1700-1763) oil on canvas of an Arabian horse and groom, is an early example of a British horse portrait. Horse portraits did not exist in Britain before the arrival of eastern horses. The equivalent of modern-day Porsches and Lamborghinis, the imported horses were status symbols and huge investments. Every owner of an import or their offspring would have wanted a portrait to hang in pride of place in their stately homes. Horse portraits differed from previous paintings of horses with humans. The horse takes center stage. The horse is noble. He stands taller than the human. His beauty is exalted. His eye is intelligent. Our horse is the image of an elite athlete, with four strong legs under him, fast, and graceful. He wears a racing saddle of the early 18th century. His dramatic mountainous backdrop appears to be the Brecon Beacons. The horse stands out, as monumental as the landscape, heroic.

Lot 764, Manner of John Ferneley (British 1782-1860), oil on canvas of three horses and riders

Lot 764, Manner of John Ferneley (1782-1860) oil on canvas of steeplechase race with three horses and riders taking a fence, identified as Mr. Ben on Dux, Mr. Lowther on Blatchington, and Mr. H. Preston on Clarissa, occurs nearly a century later. In this painting, the development of the English Thoroughbred is discernable. The three elegant horses are built for speed and agility. The dominance of the Turkoman blood is evident, the horses are taller, longer, and leaner, with lower-set tails and straight profiles. The finely colored painting shows the horses’ sculptural physique and the high gloss of their coats. Their long legs flash as they race over the obstacle. They are horses bred to run, enjoying what they do best. An early 19th century painting, all three subjects would be registered Thoroughbreds, and every one a descendant of the eastern imports, and specifically of one or more of the foundation stallions. It is possible that the horses are not the only pedigreed lot in this painting, however, as Ferneley frequently painted the Lowther family. William Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale (1757-1844) was a famous huntsman who owned the Cottesmore pack of foxhounds, one of the oldest in Britain. The Mr. Lowther who looks out at us from this painting just might possess a King Alfred pedigree.

By Pook & Pook Inc

Copyright © 1999 - 2025 Pook & Pook Inc. All Rights Reserved.

- Arts Foundation of Cape Cod Assembles Artwork From Top Artists for Its Annual Deck the Walls Auction

- WINTER AUCTION OF JEWELRY & TREASURES COMES TO TURNER AUCTIONS + APPRAISALS ON DECEMBER 13

- Rafael Osona Holiday Auction Features Fine Art, Jewelry & Maritime Works

- Post-Auction Press Release, Americana Auction, October 1,2,3, 2025 at Pook & Pook

- TURNER AUCTIONS + APPRAISALS PRESENTS THE GLADYNE K. MITCHELL COLLECTION ESTATE ON JULY 19

- Celebrate American Heritage with Dana Auctions’ January 25 Antique and Vintage Quilt and Textile Auction

- Exciting Online Auction from Rafael Osona Auctions - Exceptional offerings across multiple categories

- DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER: FINE JEWELRY, DIAMONDS & MORE COME TO TURNER AUCTIONS + APPRAISALS

- TAKE TIME OUT TO VIEW SPORTS MEMORABILIA, COMING TO TURNER AUCTIONS + APPRAISALS ON AUGUST 17

- Rafael Osona Announces Two Day Auction, Aug 3 & 4, 2024 Americana, Fine Arts, Historic Nantucket, Décor ~ Saturday, August 3 The Marine Session ~ Sunday, August 4 Open for Bidding ~ 1000 Lots ~

-

Antique Toy Auction at Pook & Pook Inc, with Noel Barrett

-

Sporting Immortality

-

The Collection of Mrs. John Gutfreund – Murray House, Villanova, Pennsylvania

-

Leonora Carrington Oil Painting Sells for More Than Twice the Asking Price in the Latin American Art Auction Hosted by Morton Subastas in Mexico City

-

Peter Tillou Collection Highlights Litchfield Auctions’ 25th Anniversary

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB